The making of Art History Remixed

by Gabriel Virgilio Luciani

When I took on this role, I promised myself to employ a critical approach to art history and its canonical, euro-centric implications. If they consider you a part of Art History (notice the capital letters) then you are ratified as an artist of value and renown. Who has been excluded from this canon? Why? Who decides who fits in the canon and who doesn’t? These are the angles I approach my lectures with. For example, this block on Body and Limits included a lecture on the history of European performance art in the 1960s-1990s which had to be complimented with a second lecture on performance art coming from voices relative to a more contemporary and non-Western landscape. Instead of omitting the beginnings of performance and its European roots, I decided to include both in this block. This way, we are provided with a more equalised, zoom-out perspective that crosses a diversity of geographies and epochs.

For the second lecture, I was allowed more flexibility and also had to embark on a new journey that included voices I am personally more passionate about. And this is essential to teaching: you have to love your material and that permeates through the entire class. But, with the second lecture comes more difficulty. As previously mentioned, accurate research is critical to what I do. And there is incomplete information regarding many artists I’ve wanted to include. Think about it: the careers of Marina Abramović and Gina Pane have been heavily documented. There are exhaustive accounts of what they’ve done and precise information about their entire body of work. The same can’t be said about Mboko Lapiki, Raeda Saadeh or Nástio Mosquito.

With that, some inferences I have to make myself. If I know the artist personally, I can engage in dialogue with them which helps sculpt out the content I end up transmitting in class. But this isn’t always the case. Sometimes my curatorial intuition comes to the front, and I have to make deductions drawing from what I know about art, artists, how they work, their sociopolitical contexts and what I personally feel. This is tricky, given that some of the information comes from a place of subjectivity. But this is the forever looping contradiction of teaching art history, or any history: there will always be a margin of interpretation that we have to account for. And this is why I often suggest that the audience also participates in making conclusions regarding the pieces we see in class.

Teaching global art history is an undertaking I’d never thought I’d have the level of confidence for. The response-ability, flexibility, omnipresence and panoramic sensibilities one has to have is the greatest challenge; yet the most exciting one.

The artists I have the opportunity to research given a new theme or focus is like exploring a new country or culture you haven’t had contact with. You dive into worlds that are so specific, some of which require so much searching to actually find. This can be the rough bit: finding information, and more importantly finding accurate information.

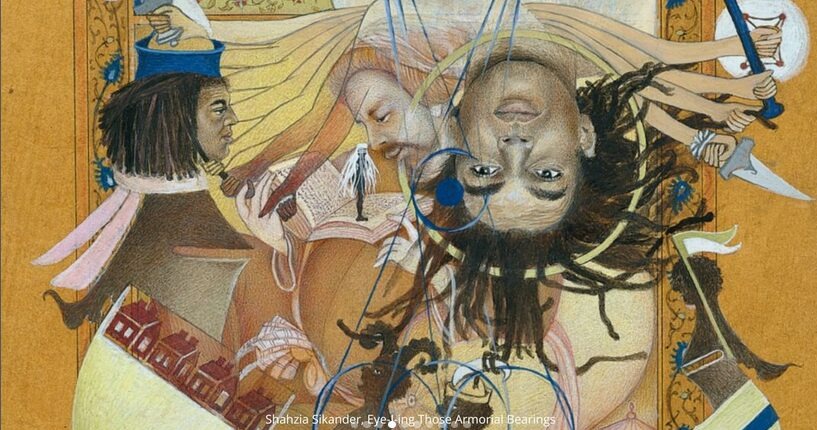

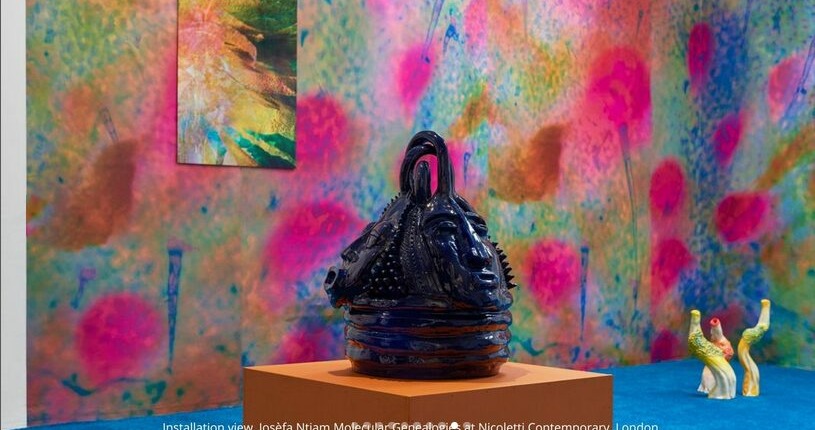

Photos (clockwise): Gabriel Virgilio Luciani, Gabriel during Art History Remixed class, a sample of artists presented during class: Shahzia Sikander, Josèfa Ntjam and Allison Janae Hamilton respectively, and students during class by Fiore Vink.